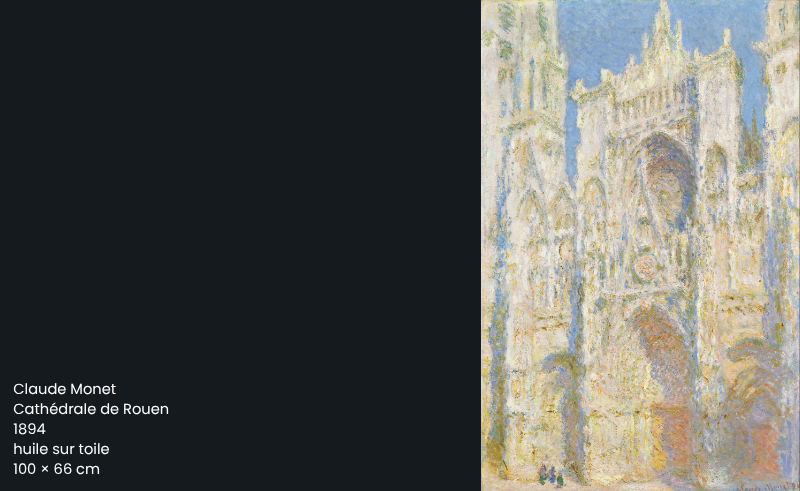

Claude Monet captured more than just landscapes—he captured light, air, and time itself. As the founding father of Impressionism, his paintings offer a window into fleeting beauty: a shimmering sunrise, a garden in bloom, or the changing surface of water at different times of day.

Born in Paris in 1840 but raised in Le Havre, Monet grew up near the sea and began sketching as a teenager. After serving briefly in the military, he returned to France to pursue painting seriously—studying in Paris and breaking away from academic traditions.

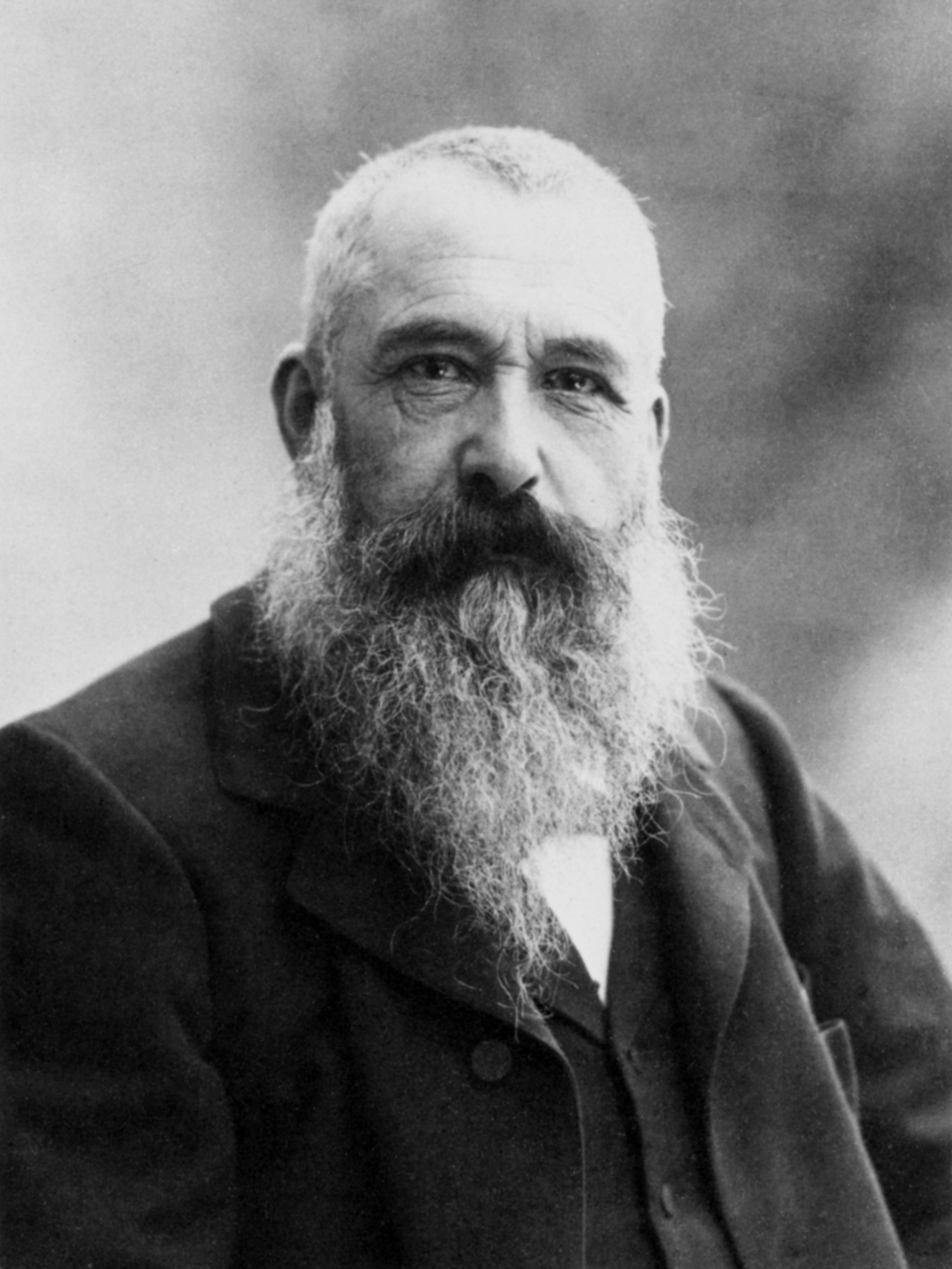

He began painting outdoors—en plein air—to better capture the nuances of light and atmosphere. His 1872 painting Impression, soleil levant gave the Impressionist movement its name.

Monet’s dedication to natural light led him to paint the same subject again and again—haystacks, cathedrals, lily ponds—each time in different weather or light.

French uses the noun "lumière" to describe “light,” one of Monet’s greatest obsessions:

Did you know? When Monet’s Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise) was first exhibited, a critic mocked it—coining the term “Impressionist.” Monet and his peers embraced the label.

Monet’s brushstrokes are quick, layered, and alive. He didn't aim to paint objects as they were—but how they felt in that moment. His gardens, water lilies, foggy mornings, and riversides invite viewers into a world of sensation and movement.

Impression, soleil levant (Impression, Sunrise)

1872

The painting that started it all. A quiet harbour scene in Le Havre, with the sun rising in misty orange haze. This work gave Impressionism its name and set the tone for a new artistic vision. You can see it at the Musée Marmottan Monet in Paris.

La Gare Saint-Lazare (Saint-Lazare Train Station)

1877

A smoky, bustling train station in the heart of Paris, where steam and iron meet sunlight. Monet painted it multiple times, capturing its ever-changing energy. Several versions are at the Musée d'Orsay.

Les Nymphéas (The Water Lilies)

1897–1926

Perhaps Monet’s most famous series, the water lilies are meditative, dreamlike, and vast. Painted in his garden at Giverny, they offer a sense of timeless beauty. Many are on view at the Musée de l’Orangerie.

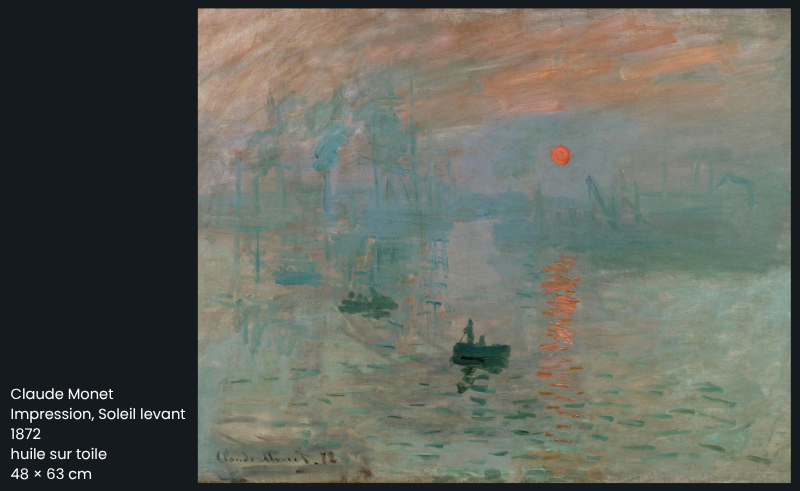

La Cathédrale de Rouen (Rouen Cathedral Series)

1892–1894

Monet painted this Gothic façade over 30 times in different light and weather. The result is a masterclass in perception. One version hangs at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

French vocabulary:

Monet’s later years were marked by personal losses and failing eyesight due to cataracts. Yet, he kept painting—often from memory or blurred impression. The water lilies became more abstract, almost mystical.

He once said: “Je veux peindre l’air dans lequel se trouve le pont.”—“I want to paint the air around the bridge.”

His legacy is not just about technique, but a tireless devotion to beauty, nature, and light—no matter the obstacles.

Grammar tip:

French prepositions like "dans" and "autour de" help describe spatial relationships. For example: "l’air autour du pont" – the air around the bridge.

Monet’s masterpieces are found in museums across France, the US, and beyond. Visit the Musée de l’Orangerie, Musée Marmottan Monet, or explore his works online via Google Arts & Culture. You can also tour his garden in Giverny—in person or virtually!