Before there was Impressionism, there was Manet. With his fearless brush and striking contrasts, Manet challenged artistic conventions and paved the way for modern art. His work shocked, intrigued, and ultimately transformed the French art world forever.

Born in Paris in 1832 into a wealthy family, Manet originally studied law before following his true passion: painting. He trained under a traditional master but was soon drawn to a more daring vision—one that embraced modern life and rejected the stiff rules of the art academy.

Manet’s paintings of café scenes, street life, and ordinary people defied expectations. His loose brushwork and controversial subjects—like a nude woman meeting the viewer’s gaze—shocked audiences and critics alike.

Though often grouped with the Impressionists, Manet never considered himself one. Still, he exhibited alongside them and was a key influence on artists like Monet, Renoir, and Degas.

The French word moderne means “modern”—a perfect word for describing Manet’s groundbreaking approach to painting.

Did you know? Manet’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe caused outrage in 1863—but it also sparked a revolution. Without Manet, there may have been no Impressionism.

Manet captured Paris as it was: lively, messy, human. His subjects weren’t idealised—they were real. He often painted people he knew, including actors, writers, and working-class Parisians. His sharp contrasts, dark backgrounds, and expressive faces created scenes full of life, drama, and intimacy.

Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass)

1863

Two clothed men, a nude woman, and a picnic in the woods—this painting caused a scandal at the Salon des Refusés. But Manet wasn’t seeking shock for shock’s sake—he was questioning what art could be. You can see it at the Musée d'Orsay.

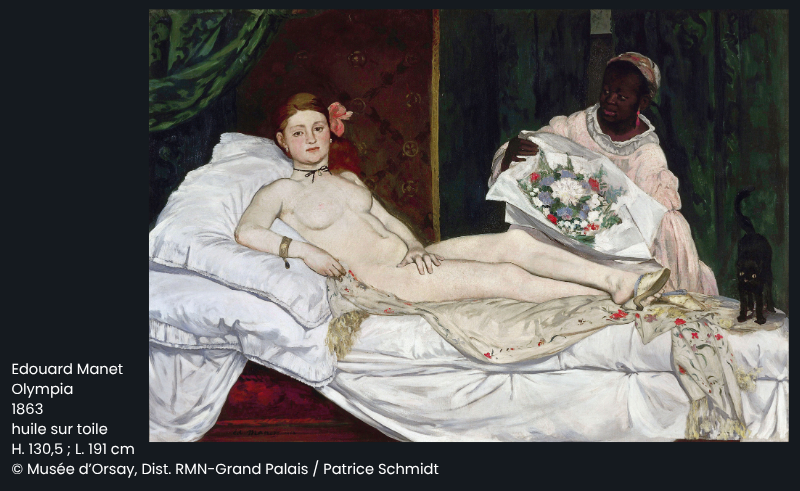

Olympia

1865

Another scandalous painting: a reclining nude with a direct, unapologetic gaze. It referenced classical works, but with a bold modern twist. It’s now celebrated as a feminist and artistic milestone. Also on view at the Musée d'Orsay.

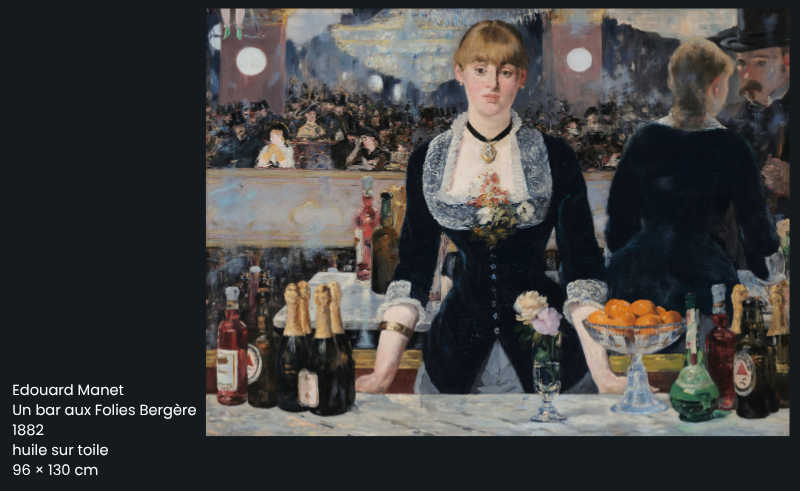

Le Bar aux Folies-Bergère (A Bar at the Folies-Bergère)

1882

Manet’s final masterpiece. A barmaid stands behind a marble counter, lost in thought, while a mirror reflects a blur of lights and faces. A hauntingly modern portrait of urban life. It hangs at the Courtauld Gallery in London.

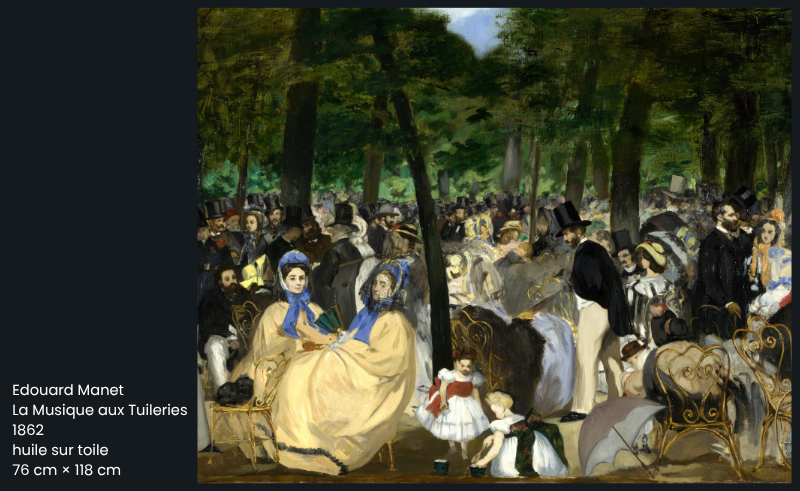

La Musique aux Tuileries (Music in the Tuileries)

1862

A lively crowd scene in a Parisian park, filled with fashionable figures and dappled light. Look closely—you’ll find Manet himself among the guests! See it at the National Gallery in London.

French vocabulary:

Manet faced declining health in his later years, eventually losing a leg to complications from syphilis. But he never stopped painting. In his final months, he created tender still lifes of flowers—works full of light, colour, and grace.

He said: “Il n’y a pas de lignes dans la nature.”—There are no lines in nature. His fluid style and bold vision continue to inspire generations of artists.

Grammar tip:

The expression “Il n’y a pas de...” is used to say “There is no...” in French. Note how “de” replaces the article after a negative: Il n’y a pas de lignes – There are no lines.

Manet’s masterpieces live in galleries around the world—from the Musée d'Orsay in Paris to the National Gallery in London. You can also discover his work online via Google Arts & Culture.